3D concrete printing aims to speed up the construction process while saving on material and labor costs.

It’s always fun to see the old mix with the new—especially with concrete (no pun intended). But hearing that concrete can be “printed” with a giant robot required a double-take. After watching the new technology in action, it’s possible we’re coming up to an era where construction companies will be asking for their concrete to be printed, not poured.

Background

The journey to understanding 3D printed concrete begins with a visit with Scott Denney, PE, Executive Project Developer at the West Jordan office of Pikus Concrete. The company’s 20 years of experience in the structural concrete construction industry led them to pursue innovations in 3D concrete printing, offering that as a solution for interested clients. A week later, James Lyman, CEO/Owner of Mudbots, is showing off his company’s 3D concrete printing at their Midvale facility. Lyman, a former contractor, ran his own construction company in Nevada before branching into several automation companies and devoting resources to take this technology to the next level. He understands that accessibility and innovation are key for 3D concrete printing to become mainstream. But how does 3D concrete printing work? Much like any other type of 3D printing, computer systems guide the nozzle to “print” concrete in a predetermined pattern—wall, flower pot, bench, virtually anything.

The printed concrete cures at a steady rate as the printer makes its various passes, creating sturdy structures both big and small that are safer on two fronts: Since the printer takes up the bulk of labor, injuries decrease. The finished buildings are also safe due to PSI strengths ranging from 600 to 12,000. Add to that the fact that the structures can be reinforced with rebar or additional concrete, and what is left is a safe, sturdy building.

As with other innovations, 3D concrete printing aims to solve a host of problems— speed and cost, all while expanding architectural creativity.

Time is Money

Pikus can print a layer of the material (typically 10 mm in height by 40mm in width) at roughly one foot per second. Denney says, depending on the layer dimensions, this can amount to almost one ton of material per hour. You’d be forgiven for thinking that things are operating at warp speed as it hums along—it’s a lightening-fast print.

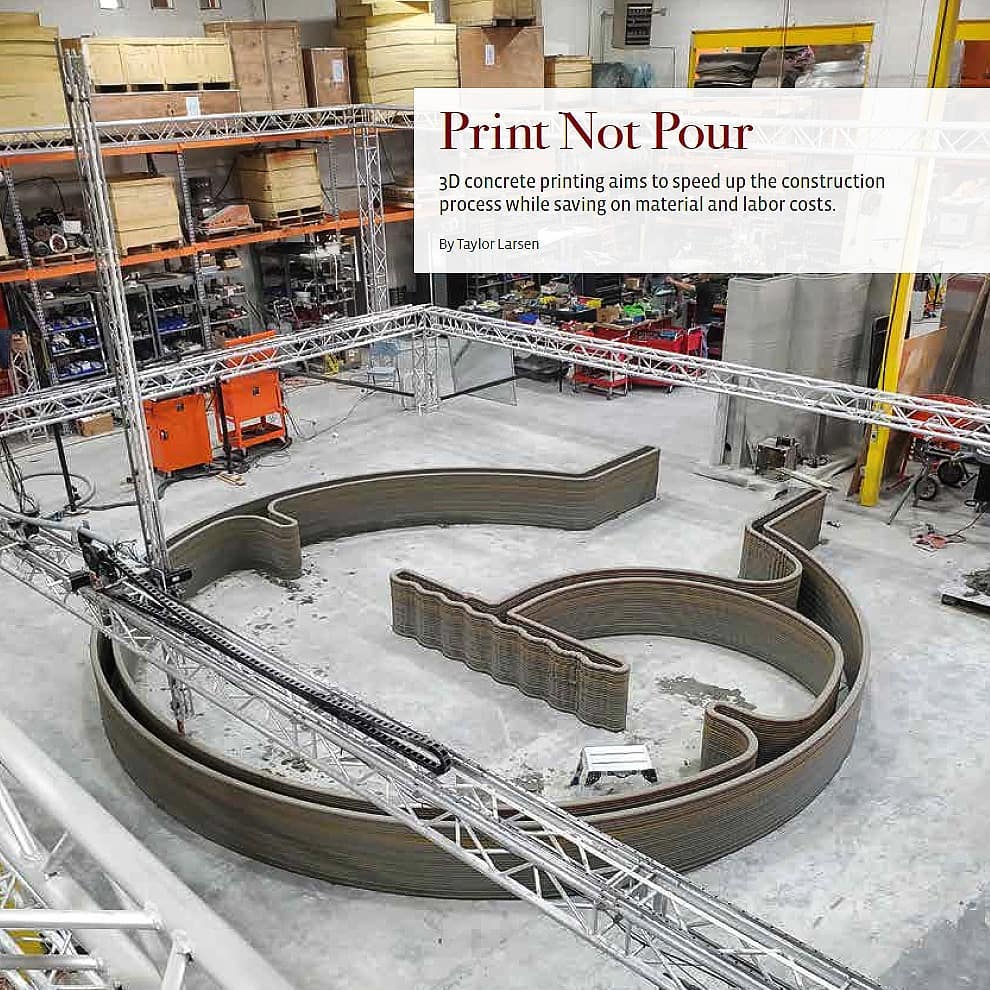

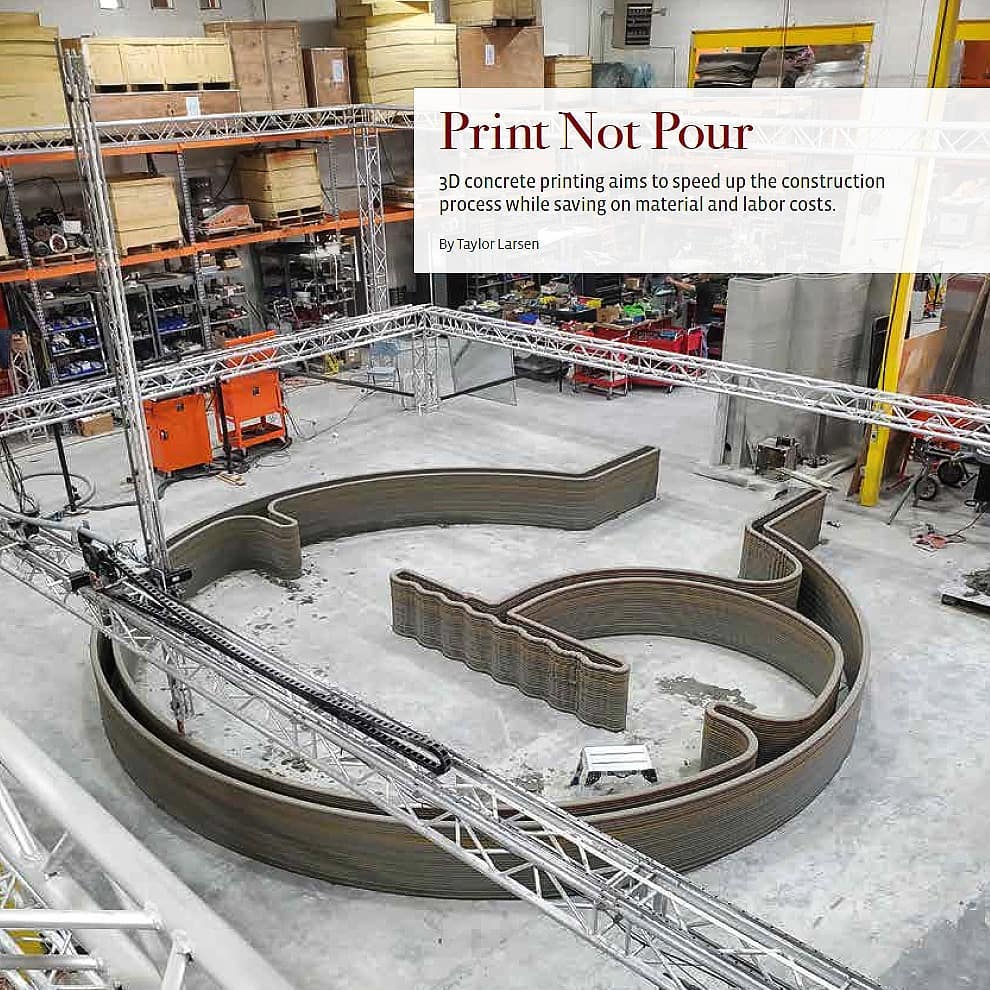

Where Pikus uses a large, powerful machine capable of quickly printing out different elements, Mudbots’ 3D concrete printer is more nimble and was made with on-site construction in mind.

“We knew we needed a machine that could be transferred from site to site and be easily assembled,” he says as he demonstrates the machine’s unique construction. Wheels can be quickly installed on the bottom after a finished print and moved to the next location. After the work is done, the aluminum-trussing, 50-foot by 50-foot by 10-foot printer can fit into a 20-foot trailer and be set up or taken down by a small team in just three hours without needing cranes or other equipment.

With belt-tightening in both the private and public sectors sure to happen as the latest byproduct of 2020, the time savings in concrete printing is directly equal to money saved. It advertises itself as capable of saving 70-percent of the time needed to build a comparable structure with traditional methods like wood framing and ICF. According to Lyman, the printer saves on labor, too—up to 70 percent by “employing” a robot to do the work. Necessary materials are readily available at construction and concrete-speciality stores. As Lyman says with a wry smile “You’re just paying for sand, lime and cement.”

Hot Market

Some owners and contractors in various industries are giving it a whirl. Pikus had some recent success with their prints in landscape architecture after being approached by Wasatch Residential Group about creating features for the Anthology at Vista Station Project.

“They were excited about the opportunity and had us coordinate with LoftSixFour to incorporate the printed objects into their current design,” Denney says. After prototyping a few different elements, “We ended up printing and installing the different elements for the BBQ stations, firepits, raised flower beds and seat walls.”

Mudbots is currently working with Habitat for Humanity to build houses with the 3D printed concrete. At half-a-cent per cubic inch in cost, this could be revolutionary for affordable housing, according to Lyman.

Concrete printing has the potential to be more eco-friendly than other forms of construction, too. With geopolymers, concrete emissions can be cut significantly from Portland cement while extending the design life of the material. Shrinkage from transporting materials and labor can be significantly decreased as things are fabricated on-site. Add in the fact that concrete is recyclable, and suddenly 3D concrete printing may as well be printing out the solutions to many of today’s challenges.

Architectural Renaissance

An undervalued strength of 3D printing is the ability to create customized shapes and dimensions at a similar cost to the standard shapes and sizes. Parametric design will allow individuals to tweak and personalize the pieces to their exact liking without the costly design and prototyping process.

It’s this idea that has both Denney and Lyman excited for architects and other designers, who will now be able to envision an unconstrained future.

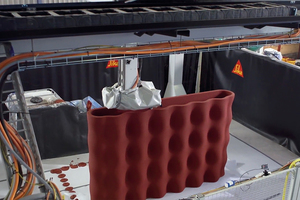

Lyman shows off a project being done by a university in Arizona in the warehouse. The university team is printing a house, but it’s more Star Wars than suburbia. The rounded walls and interesting angles making it look futuristic—but the key is that this building is tangible and not just a computer rendering.

“Architects want the freedom to do stuff like this,” Lyman says, pointing into the printing shop window to that printed structure. “They’re yearning to get off of this [box-shaped] pallet—trying to get square stuff to look pretty.”

Denney adds to that by saying, “What we would really like to have happen is for designers to understand the potential and collaborate with us to develop their own products. There are experts in architecture, structural [engineering], landscapes and arts, who know where this technology would best help them.”

Will It Take Off?

While Denney sees a gradual acceptance in various forms like printing lost formwork, Lyman feels like this technology is ready to build commercial structures and houses. He sees how an increased understanding of the technology’s capabilities will drive this innovative work.

“Will the building department accept it? Will it meet code?” He asks, albeit rhetorically, of 3D printed structures. The answer to his question is “yes” on both counts. “Structural engineers are the authority in those states to say that these meet code. They understand how it works, they aren’t scared.”

Both see this as the future of construction. Whether or not others take them up on the challenge to be pioneers in 3D concrete printing, Denney and Lyman know that the future is printed in concrete.

About the Author

This article is written by Taylor Larsen

Read the original post here.